"Boy, We Drink Joe Louis."

When ESG Investing Is All We Got

It was bright on June 29, 1978. It was always shining on that date. Once I had my clothes on, I remembered it was John Gardner’s birthday, which always felt like a holiday. I had a construction paper card my mother corrected for anatomical accuracy before she approved it. I was dressed and prepared to be useful.

“Put it by his plate,” she said, silently and scarily beautiful, and I did. There was always a bit of Daisy Buchanan in my Old G, which is how we said “my moms” back in the Chi.

She was a four-foot-eleven big mouth with tiny bits of uppity betraying her light-skinned Black Boheme thing, such as her in a sun dress and an up-do, 1960s Josie and the Pussycats shit, in front of the stove cooking breakfast for my father. A birthday breakfast we wouldn’t be eating with him, as kids were sent out of the house when adults wanted to be real people back then.

She wasn’t looking at me. She was cold. John and Wally were somewhere arguing and fighting and breaking something—over nothing. In that house, it seemed the walls argued with the floors and the ceiling. Usually, she’d call them into the kitchen and beat them with whatever she used to stir the pot, but she did not react.

“John Gardner is coming over,” she said, sneering. “To see his son on his birthday.”

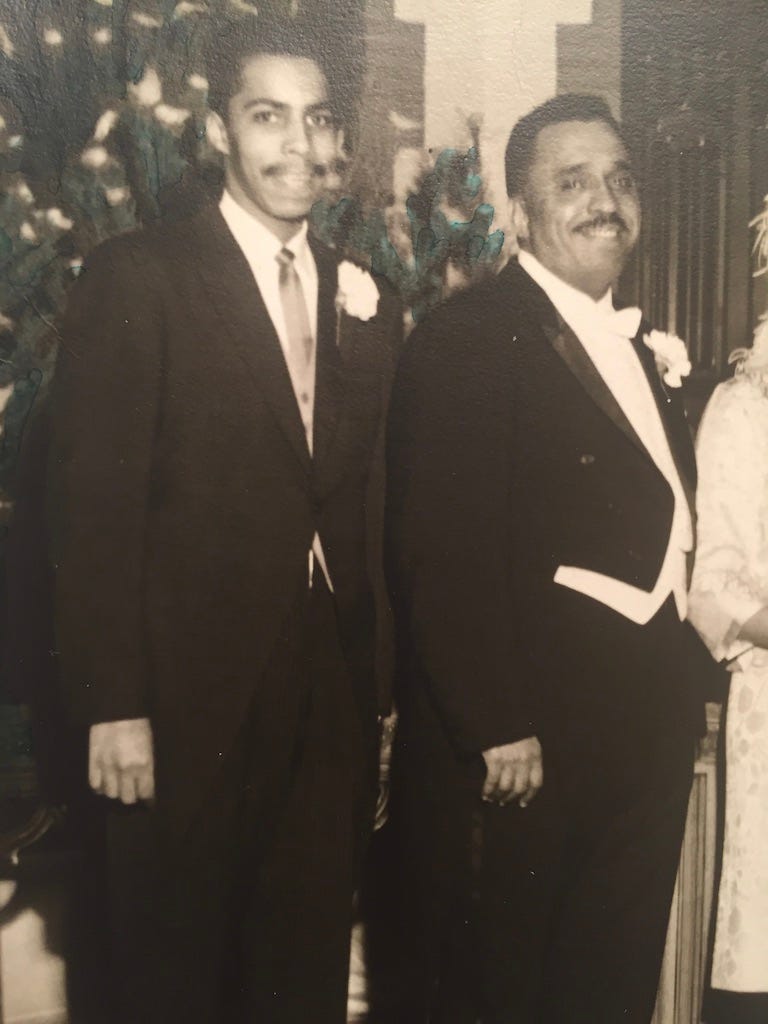

My parents were raised Black Rich in Washington Heights, where “they don’t even let Negroes live ‘round there,” so you know it was good. Raised as a couple of rebellious Black teenagers in a restrictive covenant neighborhood, they taught us to think of ourselves as poor. Their generational wealth experiences were well hidden from us. Some of those experiences left scars on my pop’s psyche.

“Go get milk. Keep the change. Stay out of the house.” As she finally walked down the hall to beat the snot out of my brothers, I had two options for milk in Washington Heights in the Chi in 1978.

From the corner store, my parents’ corner store growing up, where everyone knew me before I was even born, and they won’t even sell me candy if she doesn’t allow it. “I don’t want Rosalita mad at me, Lil Man.” She grew up terrorizing the neighborhood before I was a thought. That was locked down. I thought of Chicago penny candy and illegal bottle rockets for the 4th. I needed a deal on milk.

Hank’s Liquors, on 95th Street, east of Halsted, down the block from the Road Runner snack shop that dealt those same illegal fireworks, advertised Carnation-brand milk, and on sale. The same milk as in the ads during Saturday Morning cartoons. Looked like a good brand. It made white folks in the commercial happy enough. Hank’s was a hangout for neighborhood denizens in the “packaged goods” days when Washington Heights was Black and Jewish. That was the term for alcoholic beverages when polite people didn’t admit their uncle’s “medicine” wasn’t medicine. A pre-teen could purchase cigarettes and booze for his parents’ backyard BBQ from there, and no one said anything but “How’s ya mama?” Hank had a back door with a sign that read PRIVATE and always some grown-up noises behind. Hank’s was Black-owned since forever.

Hank was my fella who let me purchase the wrong milk.

I get the milk and run back home, and my father is seated at the table, still in his Fire Department uniform. He’s looking at my card. He’s smiling. He always liked my work. Ma is finishing breakfast. I put the milk on the table, as in the commercial with the white folks, just right on the table, where it could get warm, and the Old Man looks incredulous at the carton. He had a bit of a grin and seemed in good humor.

I felt the slap to the back of the head.

“Boy,” she said through gritted, gnashed teeth. “We drink Joe Louis.”

She shoved the milk carton back at me, and I already felt my profit dwindling when I returned the wrong brand to Hank, received my refund, and ran to the corner store. Everyone there was laughing. Rosalita called to ensure I left with the right milk; everyone knew Rosalita. The entire neighborhood laughed; who knew why? My first bit of improv, perhaps.

As I returned to the crib, the nicest Lincoln from the fire department officer’s pool was parked outside the house. Inside was GG, Grandpa Gardner, at the table where I placed the milk. GG hugged me and waited for his cheek kiss. He never waited long. He even smelled like money.

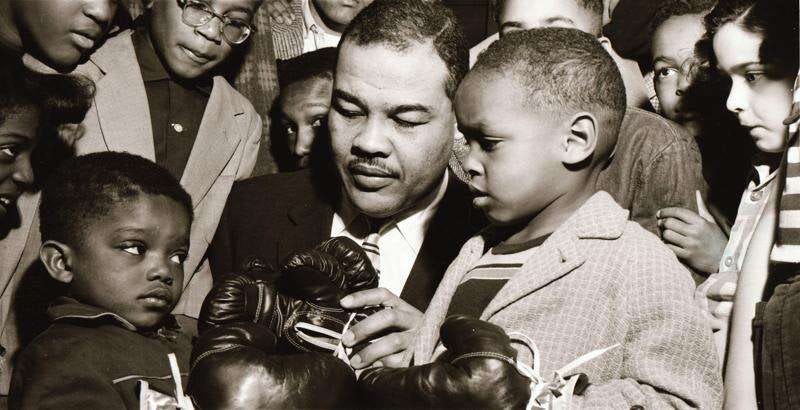

“Ah,” my grandfather, the Feared One, said. “Joe Louis. He was by the other day.”

“Oh,” my father said, dutiful, carrying on conversation.

“Needs money.”

“Don’t we all.”

“Go outside and play,” she said coldly. She didn’t look at me. She was too busy protecting her husband from his big, bad, Black Capitalist daddy. There he was, a kid himself, at the same table, hearing all the same shit again, and on his birthday. I felt so bad I nearly gave back the change from the bone she gave me for the milk.

Instead, I got ten Big Bols, 25 Albers fruit chews, and some of those iced butter cookies in big glass jars from Charlie Wilson’s grandma’s back porch, where she illegally sold candy. And I got those bottle rockets from Road Runner without a Firefighting Gardner aware.

Mr. Williams from the Corner Store—also, always Black owned, sans bottle rockets—explained to me sometime later that Grandpa Gardner was an investor in Joe Louis Milk, a branded milk company created by and for Joe Louis, the National Treasure and enemy of the Internal Revenue Service, to keep him afloat as the United States of America betrayed him. Joe and his folks, which included GG, treated it as Joe Louis’s service to the Black American community. Still, it was really for Joe, who was hounded into poverty by the government, and boxing, and blackness in America. This truth made me proud of my grandfather and made me feel bad for my father, for whom normalcy would be my mother’s most genuine, fleeting gift to him. Imagine that. Did Joe Louis stop by? Oh, how is he? Pip pip, cheerio. Like it’s normal. Needs money. Don’t we all? Those people I was born to. Lordy.

Growing up, I ate my cornflakes in the Black Man’s milk; my GG had everything to do with it. Those moments came with scars and costs. That’s why you’re reading Bronzeville Books, not Simon & Schuster.

Wishing you candy and bottle rockets. Happy New Year.

Mayor